by Gary Alexander

October 14, 2025

First, let’s celebrate the fact that the government shutdown has spared us from the wildly premature and often inaccurate monthly jobs report, usually deposited in our inboxes on the first Friday of each month. We can also celebrate avoiding this week’s often-misleading inflation data, but rising costs are still visible.

Rather than grinding the numbers released in this monthly cycle of algebraic mumbo-jumbo released by our government, we’re usually better informed, in my view, by studying history and the long-term trends.

In that spirit, let me reflect on the Federal Reserve’s role – and mixed record – since its founding in 1913 by a gaggle of business leaders who were mostly trying to avoid bailing out the nation’s banks in another Panic of 1893, or Panic of 1907. Let the government solve the next crises – the Panics of 1920 and 1929!

The Fed prides itself on its independence, being non-political, well above the pleadings of special interests and powerful politicians, but are they really? Being independent, they remain open during a government shutdown, but if they were as “federal” as their name implies, are they essential workers?

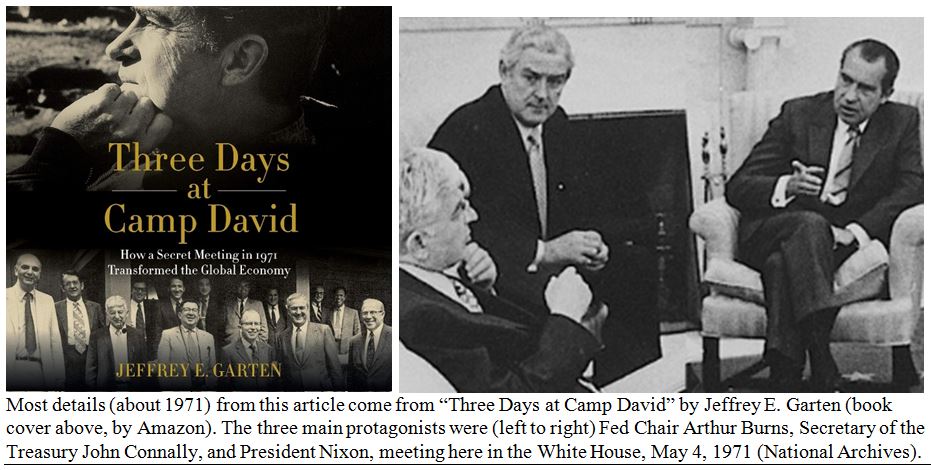

I’ve just finished a book about the Nixon Era’s New Economic Plan (NEP), comprised of a revolutionary series of eight huge interventions in the markets, hatched over a long weekend in Camp David, August 13-15, 1971. In this drama, as it unfolded, President Nixon battled royally with Fed Chair Arthur Burns.

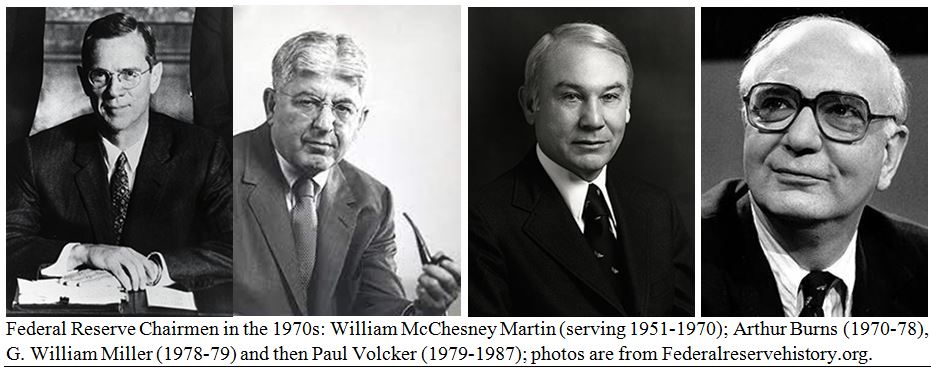

President Nixon nominated economics professor Arthur Burns as Fed Chair this week 56-years ago, on Friday, October 17, 1969. Nixon was tired of fighting the seeming “Fed Chairman for Life,” William McChesney Martin, who had held that office for 18-years when Nixon was first inaugurated in 1969.

Nixon announced his intention to nominate Burns in October of 1969, and a few days later, the two gents held a private meeting, as recorded in the now-famous Nixon Presidential tapes. See if you can identify the similarities between Nixon taunting Burns and the current tweet tiffs between Trump and Powell.

Nixon (to Arthur Burns): “My relations with the Fed will be different than they were with Bill Martin. He was always six months late doing anything. I’m counting on you, Arthur, to keep us out of a recession.”

Burns (lighting his pipe, as he often did when thinking) “Yes, Mr. President, I don’t like to be late.”

Nixon: “Arthur, I want you to come over and see me privately anytime… I know there’s a myth of the autonomous Fed … and when you go up for confirmation, some senator may ask you about your friendship with the president. Appearances are going to be important, so … get messages to me…”

Sure enough, in Burns’ hearings, Senator William Proxmire (D-Wis) asked if Burns would maintain his independence or “become a kind of handmaiden to the Treasury.” Burns answered with double talk, as Nixon had counseled him: “I assure you that I will always do what I think is best and what is sound for the nation, without regard to any consideration of partisan or political or extraneous advantage.”

After Burns passed his confirmation hearings, President Nixon congratulated him in a press conference:

“As you all know, the Federal Reserve is independent… I respect that independence. On the other hand, I have the opportunity as president to convey my views to the chairman… I respect his independence. However, I hope that independently he will conclude that my views are the ones that should be followed.”

Privately, Nixon was more forceful and less of a stand-up comic. In a cabinet meeting on April 3, 1970, Nixon slammed his hand on the table, telling his aides, “When we get through, this Fed won’t be independent, if it’s the only thing I do.” (Are you beginning to see the Trump/Powell connections yet?).

One major bone of contention between Burns and Nixon was that Nixon wanted more money supply and lower interest rates, “easy money,” while Burns demurred at first. Another conflict between the two was that Burns favored wage and price controls, which Nixon had consistently derided. As a young lawyer in Washington DC during World War II, prior to joining the Navy, Nixon had worked as a junior attorney in the tire-rationing division of the Office of Price Administration, an experience that left him distrustful of any price controls as an efficient way to contain prices, leading invariably to rationing and black markets.

Burns was no monetarist, he believed more in “cost-push” inflation, where corporations and unions push prices and wages higher, so he favored wage and price controls, something anathema to Nixon – at first.

In 1971, the Democrats controlled Congress and, like Burns, they generally favored price controls, so on Thursday, August 13, 1970 – exactly one year before Nixon’s team decided to impose wage and price controls, the Democratic-led Congress sided with Burns by promoting wage and price controls as part of the Economic Stabilization Act, in a veto-proof rider to laws protecting national security, giving the president no chance to veto the measure, but Nixon declared that he had no intention to use that authority.

This fueled policy wars with Burns over price controls and monetary policy, causing such a rift between Nixon and Burns that Nixon once considered enlarging the size of the Federal Reserve Board – packing it with his supporters and thereby eliminating the Fed’s independence, making the Fed report to Secretary of Treasury John Connally, a strong-armed Nixon enforcer, the wartime consigliere Nixon fully supported.

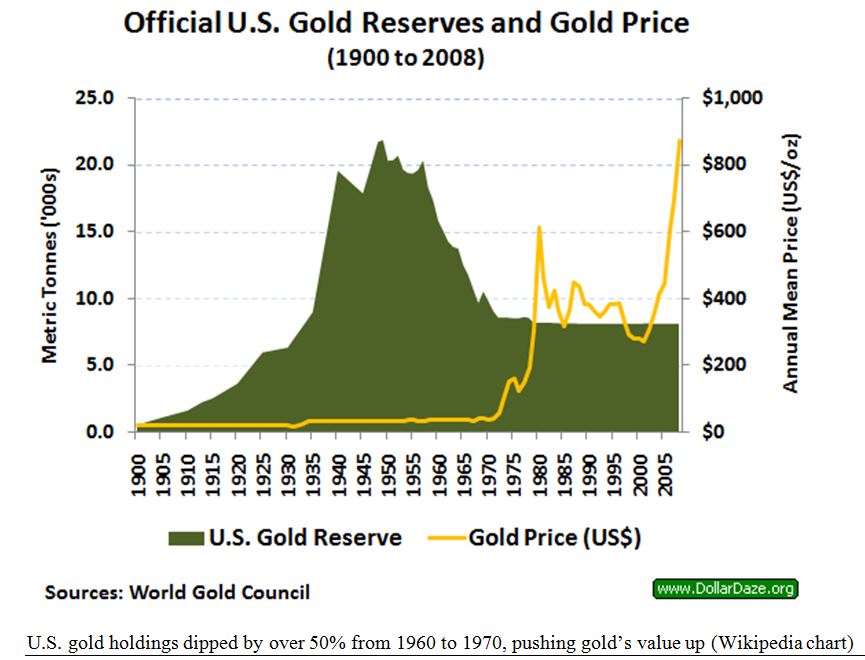

As I reported here last August, President Nixon invited 15 key economic aides to join him at Camp David over a long weekend following the business week of August 9-13, when U.S. gold in the Treasury was being rapidly depleted by foreign investors and governments redeeming dollars at the Treasury “gold window” at just $35-per ounce. In that one week, America sold off nearly one third its gold hoard, then worth $4-billion overall. And America faced its first merchandise trade deficit in 78-years, since 1893.

Gold was flying out of the U.S. Treasury – mostly to European central banks – throughout the 1960s, threatening to wipe out all our gold by summer’s end. Speculation was rife. The German Mark rose to a 20-year high. Future Fed Chairman Paul Volcker said we must act now: “The decision would not wait.”

Graphs are for illustrative and discussion purposes only. Please read important disclosures at the end of this commentary.

In August 1971, Nixon gave in to “temporary” wage and price controls “for 90-days,” but price controls were still being set and enforced (when possible) three years later, when Nixon resigned the Presidency.

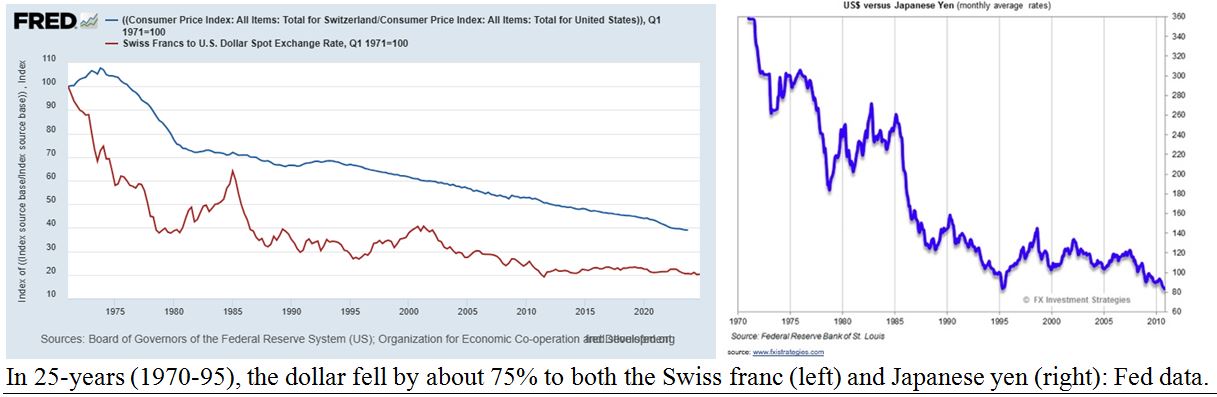

Arthur Burns later gave in to the pressure of raising money supply, at first to avoid a recession in Nixon’s 1972 re-election year, but then the OPEC oil supply shock in October 1973 sent inflation rates off to the races. When Nixon left office in 1974, the inflation rate was already registering double digits, at 12.3%.

Graphs are for illustrative and discussion purposes only. Please read important disclosures at the end of this commentary.

At the end of the 1970s, President Carter nominated Paul Volcker as Fed Chairman, asking him to find some way to kill inflation, which he did, quite effectively, but it cost Carter the presidency, as Volcker’s medicine created two deep (double-dip) recessions (and super-high interest rates) from 1979 to 1982.

Since the 1970s, no president has tried to undercut the independence of the Federal Reserve anywhere near as much as Richard Nixon did, until the Trump/Powell wars of 2018-19 and now, again, in 2025.

Today, gold is over 100-times its pre-1971 price of $35-per ounce, and almost 200 times its fixed price of $20.67- per ounce before 1934, so today’s dollars are worth about a 1933 penny, or a 1913 half-penny, in terms of gold. The Federal Reserve presided over this massive dollar devaluation, while central banks in the poor (developing) nations are now creating an unofficial gold standard by trading their paper for gold.

Such are some of the sad results when 15-top money men retired to Camp David one weekend in 1971.

The Fed’s original “dual mandate” was to prevent (or intervene to end) any banking panic – and to defend the value of the dollar under the gold standard. The Fed clearly failed the first mission by causing the Great Depression to deepen, and it failed its second mandate by creating 3,140% CPI inflation since 1913.

Graphs are for illustrative and discussion purposes only. Please read important disclosures at the end of this commentary.

So, during this government shutdown, we need to ask if the 400+ PhD Fed economists are essential workers. I’d say no. Take a furlough, guys, then read some history books and change your losing game.

The post 10-14-25: Is the Fed Really Independent…or Necessary? appeared first on Navellier.