by Gary Alexander

April 8, 2025

If you’ve followed these columns any amount of time, you know I’m an evangelist for turning around our high and rising annual budget deficits before it’s too late (See March 11 on “The Magic Formula for Creating Budget Surpluses,” or last week’s second half on “Gold is Rising Mostly Due to Soaring Deficits Since 2001”), but trade deficits are a different animal. Although these deficits can depress our quarterly GDP calculations – as I explained in last week’s Growth Mail – they are not debts that must be paid off, like budget deficits, or your personal debts. Trading is simply exchanging money for goods. Both parties benefit from a trade, or they wouldn’t make the exchange. It’s just like anything you buy. If a store in Tennessee buys an appliance line made in Kentucky, there is no “trade deficit” created in Tennessee.

The archaic notion of a “favorable” balance of trade came out of an old pre-Adam Smith theory called “mercantilism,” which basically said that a nation’s wealth depended on how much gold and silver they could accrue, either from expeditions to the New World, or in positive exports to their neighbors. To create a “trade surplus” (more gold), mercantilists added tariffs or subsidized their domestic exporters.

In 1776, Adam Smith attacked this system by bringing the consumer into the picture, championing lower-cost alternatives, while his contemporary David Ricardo explained the virtues of comparative advantage, with each nation exporting those goods which that nation produced more efficiently in open competition.

Over the next 250 years, the U.S. ran trade surpluses for a century from 1870 to 1975, in our era of greatest growth, but as we moved more toward a service economy, manufacturing jobs moved overseas.

Graphs are for illustrative and discussion purposes only. Please read important disclosures at the end of this commentary.

Notice the sharpest dip in trade deficits began in the late 1990s, after the passage of NAFTA, at the same time budget deficits were balanced during fiscal years 1997-2001, so there is no correlation between trade deficits and budget deficits. Trade deficits are between corporations situated in two nations, while budget deficits are from fiscal policies in Congress financed by the Treasury. Never the twain met, back then.

Trade deficits exploded downward after 1997 at the same time we had budget surpluses, 1997-2001 (Seeking Alpha)

Graphs are for illustrative and discussion purposes only. Please read important disclosures at the end of this commentary.

In a U.S. trade deficit, the other side gets paper money, and we get goods, but both sides got what they wanted, so trading is still favorable to both parties or they wouldn’t trade. Since the 1990s, exporters grew rich with cash, just as in the 19th century America imported capital, rising from relative poverty to become the greatest power of the 20th century, but now the dilemma is that high and rising U.S. trade deficits for the last 30 years created a job vacuum for middle class blue collar worker in America (1990s Presidential candidate Ross Perot called such job losses “that giant sucking sound”), and that is what President Trump is trying to attack by seeking on-shoring and more exports through pushing tariffs on the rest of the world.

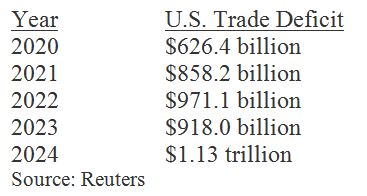

The reason for his urgency is that the trade deficit deepened under Biden, up 80% in the last four years:

Trade Deficits are Not Tariffs

Wednesday, April 2nd was pre-announced as “Liberation Day,” but it turned out to be a portfolio-killing day, too, especially after the unveiling of Commerce Secretary Lutnick’s scary chart of high tariff targets.

If enacted, these will be the highest tariffs since 1909 (bigger than the 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariffs), and 10 times the level of tariffs in place when Trump took office in January. They could become a huge tax increase via inflation and are a mega-trillion-dollar market loss so far, all based on a slap-dash series of assumptions, most notably that trade deficits equal tariffs, and all tariffs are easily quantified, by formula.

It is unlikely that most of these tariffs will be enacted, as nations will soon be lining up to negotiate lower tariffs, but there are so many specific details to each nation’s trade policies that the details resemble the ancient Gordian Knot – best solved with a saber – which in this case would be zero tariffs on all sides.

As presented, Lutnik’s New Math lined up all nations for the firing squad, without any hearing for their side of the story. For instance, Vietnam recently inherited a lot of Chinese factories when U.S. operations moved from our major foe to a more friendly Vietnam. Last year Vietnam exported $136 billion in goods to us, and they imported only $13 billion for a trade deficit of $123 billion, which the Trump team called a 91% tariff. Vietnam did the right thing, to lower their tariffs in advance, but they got punished anyway.

Lutnik’s full national tariff chart runs to well over 100 nations, some of them remote islands with few people, and every nation has a minimum 10% tariff, plus half of whatever trade deficit they ran up in 2023. Some examples of small islands include Saint Pierre and Miquelon facing 50% tariffs on their tiny exports of $3.4 million while importing just $100,000 – called a “97% tariff.” Uninhabited Australian outposts of Heard and McDonald Islands face 10% tariffs, while Norfolk Island (population: 2,188) will be hit with 29% duties. This all sounds like a Gilbert & Sullivan operetta, or a good movie spoof script.

America enjoys trade surpluses with some major nations – including Great Britain and Australia – yet they are punished, too. Our favorite economist, usually a perma-bull, Ed Yardeni, is losing confidence in Trump writing, “It’s really a shame that Trump is so willing to take a wrecking ball to the economy. It has been very resilient over the past three years in the face of the tightening of monetary policy. We are losing our confidence that it can remain resilient in the face of Trump’s Reign of Tariffs.”

Well, I’m on the fence too, for now, but I’m not so quick to throw in the towel, so I’ll close with some predictions: (1) Tariffs will not replace income taxes, as Howard Lutnick wishes will happen. The 1880s were an era of very, very small government, unlike now, and today’s nations won’t pay these high tariffs, (2) Many nations will negotiate much smaller, even zero, tariffs and will “play ball” to keep trade flowing at a more reasonable cost, and (3) the stock market will recover from the current panic loss, probably by mid-year, as GDP recovers, but (4) the doomsday press will predict another crash, and many mobs of angry, crazy folks will stage violent riots, protesting Trump’s policies and Elon Musk’s actions.

In other words, my prediction is history will keep repeating itself, and markets will revert to the norm – which is to rise.

The post 4-8-25: Trade Deficits are Not Like Budget Deficits…or Tariffs appeared first on Navellier.